Before and After:

Stories for Times Like These

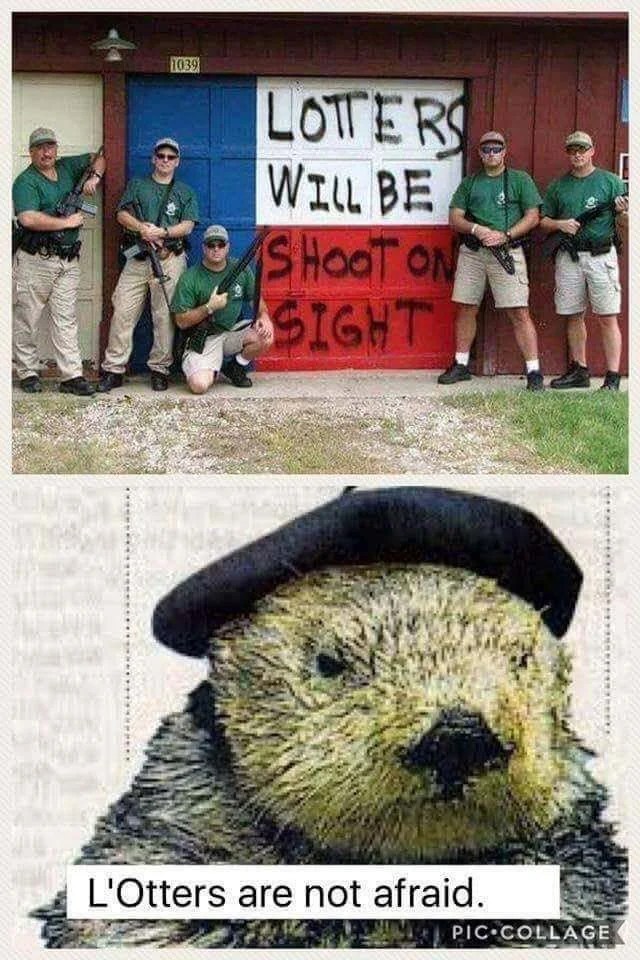

I saw the meme below in 2017. It inspired the first story I drafted for Before and After.

But I was afraid. Everything in current events was alarming to my values and family history.

In the intervening years I observed many different responses to how society was changing, and realized that the ancient curse, May you live in interesting times, was my generation’s new legacy. These stories are my answer to that challenge.

I’ve self-published before. I’m ready for an agent. Specifically, I want an agent who feels these stories in her heart and gut and also thinks they are marketable.

When I write I see everything as a movie. I hope to sign with an agent who sees strong potential to sell media rights as well as a published collection of stories. That’s also what I wish for three other available properties I’m happy to discuss. I hope this project resonates with you.

Table of Contents

(Note: Completed titles are below. Many others are works in progress. The rest are conceptual but not drafted.)

| A | A Man of the City |

| B | The Baker |

| C | The Caretaker |

| D | Dog Daze |

| E | Every Thursday Afternoon |

| F | Foxes |

| G | Girl With A Gun |

| H | Her Wooden Spoon |

| I | Inventory/Interrogation |

| J | The Jacket |

| K | The Klansman |

| L | The Lodger |

| M | Mythologies |

| N | Night, Night |

| O | Old Family Recipe |

| P | Promised Land |

| Q | Quietly, Quietly My Dear Ones |

| R | Remembrances |

| S | Schrodinger’s Jews |

| T | The Travellers |

| U | Until the End |

| V | Visions |

| W | Why |

| X | XXX |

| Y | Yes |

| Z | Zed |

| Epilogue | The Missing Letter |

Stories

A Man of the City

He was a man of the city. He knew all the small parks and had a favorite bench in each. Some were public, along paths of the myriad tourists who overran the city three seasons a year. Others were hidden, and allowed reflection, like the small, crumbling fountain in the courtyard of his local synagogue.

His daily walk connected him to his chosen home. He took regular communion feeding pigeons and watching children play, as he shared greetings with busy shopkeepers rolling up their grates, and nodded to the other strolling regulars, anonymous but familiar. Some days were aimless and silent. Others he sampled delicacies from the pods of food vendors ringing the neighborhood parks. Or in the bustling markets where hawkers shouted of the freshest produce and catch of the day. Everywhere he met smiles of greeting, the pulse of the city reflected in his brisk rhythmic steps.

Tuesday through Saturday he opened his gallery at eleven. This allowed him to rise at a comfortable hour, perform his ablutions, and be seated at the corner café for morning espresso and a hard roll, hot and yeasty, served with the proprietress’s special quince jam. As thanks, each year at the holidays he gifted figs from her distant homeland. They understood living far from their roots.

It was called Gallery Louisa, for reasons answered only with a quiet smile. The art was eclectic, a reflection of his interests in both science and the natural world. The pieces were all small, constellations of color and light on the white plaster walls that led from room to room, each with its own ambiance and focus. There were modernists and classics, simple line drawings and deft oils. The art varied in style, subject, and medium. But there was an emotional resonance. The truth of who he was, reflected in three hundred small frames, each offering a window into worlds known and imagined.

Visitors and passersby saw him relaxed, comfortable in an ancient leather armchair. A sweet-smelling pipe in hand as he reread a favorite, in the side of the gallery that felt more like a home than a store. A huge, scarred, mahogany sideboard held a weathered samovar, plus teas and tisanes for guests who lingered, asking about a particular piece, or perhaps the book he was reading, hoping to be remembered when he needed an extra dinner guest.

It was always best to make an appointment, because some travelling soprano might beguile him away. Louisa’s sign would flip quickly to Tomorrow, please…. if someone offered him a ticket or came with news of a hidden masterpiece discovered in a neighbor’s attic.

He was happy in this simple life. It suited him.

His best friend was a cellist with the local orchestra, a former professor of literature named Isabella. She’d taught for many decades, finally relinquishing the chalk for her bow, gifting herself a retirement of travels through music and their regular journeys together.

They walked and walked. Walked and talked. Walked and admired the bounty around them. Through galleries and museums. To concerts, operas, plays, and lectures. In the city and abroad. She tolerated the opera for him. He tried to appreciate her song-free stages. People assumed they had been married for years, but their friendship defined boundaries. Charm and mystery lay at the heart of their story. Their conversations sparkled with wit, wisdom, and friendship, accompanied by excellent food, and the best wines, coffees, and delights both sweet and savory. They never said goodbye, only planned their next encounter.

If you were very fortunate, you’d be invited to one of the feasts they hosted at midsummer, New Year’s Eve, and the equinoxes. A seat from one to the next was a badge of one’s insight and intellect, and a testimony to good sensibilities and character. There were never scoundrels, liars, or bullies at the table, no matter how they tried to inveigle their way in.

The meals were beautifully catered. Guest chefs vied to dazzle, locally inspired creations displayed to tempt eye and palate. Paired with selected vintages, each course was languidly savored while guests discussed culture, philosophy, and politics. Often there was a recital by the musician living in the guest cottage across the meandering gardens from the house. He was a mentor to local youth; several had been found by his knowing ear and helped by his sponsorship.

His home was modest. Built two hundred years before, on a quiet tree-lined street. The simple exterior belied the wonders he had assembled within, treasures of his travels, alone and with Isabella. Prizes from decades patiently poking in the bins of art sales and flea markets. Piles of well-worn books, long-cherished recordings of his favorite music, and photos covered most surfaces. The walls were filled, frame abutting frame, a mirror to his gallery, the curation of a long evolving perspective. One table held his pipes and a decanter of tobacco. Dark-rimmed eyeglasses in every room. Open books, catalogues, and journals invited closer scrutiny. But everything was tidy, even the odd short closet near the door that held his inevitable tan jackets, hats, and walking shoes.

Rarely did he encounter his past. When it happened, a watcher might see an inner curtain descend. A silent, but strong ward. The source might be a headline, name, or swastika in the news. A sudden blink, and he was gone. Briefly but firmly. A shell. Until the return of a careful smile that did not reach his eyes. Always a residual caution from those dark times. The shadow when he spoke of his long-dead mother, aunt, or sister. Those who cared did not ask again.

He never spoke of the early years. She knew they had been troubled. Not merely the jackbooted politics that killed so many, but knowing he was different from his peers. Partly as a immigrant; partly his intellect. Most vital, his ability to see beneath the surface of what others accepted too easily; and his willingness to ask questions, albeit quietly, that others might avoid.

He was always the charming host. Invitations were an honor. He and Isabella chose carefully for each themed party. Then they made a game of chores. I’ll choose the chef, and you do the wines. Only if I choose the dessert. And who shall we sit next to Danielle? They laughed often and richly, with a love and understanding forged by decades of trust and companionship.

He was a happy and lively conversationalist, humming favorite arias, and sharing, with a collector’s avid twinkle, recent acquisitions that might never adorn his gallery walls. Always recognizable in his muted tweeds, he made everyone feel welcome. Guests sensed he understood the depth of the world but had not been too damaged by its hard lessons. His eyes answered most of their unspoken questions.

It was a good life. He lacked for nothing that mattered and savored everything with quiet pleasure.

She saw him for the last time as she strolled the gallery with a visiting friend. He was in deep conversation about a new painting: a modern interpretation of an old favorite, Bellini’s St Francis in the Desert. He stood transfigured in the afternoon’s golden light, his waving hands awash with stories. When she heard he had been found the next morning, asleep for the last time, his glasses askew and his book loosely drooping, she thought about their last trip to Italy, and a promise to visit there again.

Another life.

The Baker

She made us laugh.

She made us laugh when it mattered most. Whether it was an impromptu story or an awkward jig, it broke the tension of our days. She made fun of us; she made fun of Them; she made fun of herself. It was just a moment, but a moment in which we felt human again. The laughter was like bread. The most basic hunger. One fed so rarely since The Upheaval.

She had the best laugh. Deep and resonant, starting from a place so low in her belly you could almost feel it being born.

I wish I could remember her jokes. There was one that started, Do you have an apple? By its end she’d built an ark out of the most unlikely objects, both those things too present and those so very absent from our grim reality. But she took us on so many magical journeys. We needed every moment of them.

I was blessed to be her bunkmate. To share hard planks where true rest was elusive. But we were at least prone. In the wee hours, when we could not sleep, we talked. She told me how guilty she felt just being alive, and for the brief moments of stolen joy she could still access. How all of her family had been taken. Disappeared. Gone for good. Though, truly, gone for bad. I am not ready to die, she said fiercely. But this strange new family we are making here, here in this madness, this is worth my life. I have no other now.

Ironically, she radiated a stillness that touched everything near her. Even the worst guards, the ones who never needed a reason to strike a blow, seemed cautious around her. That subtle deference made us feel a little less lost. A little less cut off from our former lives, despite living in a hell that made even the humblest of days past seem like paradise lost. That gave us hope. But ultimately it was the laughter. Her access to that human core that saved so many of us.

Someone asked her once where they came from. The stories. She cocked her head and looked away. Enigmatic and deep. Bewitched by memory. Finally she answered, I learned to shut up and listen. They stared. She added, The sparks are hidden. If you’re quiet they’ll tell you their secrets. The secrets write the stories. They’re what we live on now. They help us fill the holes, as best we can. They are holy food.

She was quiet for a moment, then spoke more seriously. Not with yearning and loss. But with a rueful remembering. She talked with the kind of sad knowing we shared. Of holiday meals prepared for days and devoured in minutes. Of the poignant smells of fresh laundry and real coffee. And of nipples ragged from nursing children now torn from their mother’s embrace. Of lives of joy and family and comfort long and forever gone. Of how God’s eyes had slid away from us.

There were rumors about her of course. Someone said she’d run a nightclub Before. Others said everything from a food pantry to a brothel. But we all had pasts that were suspect in the eyes of the authorities, and no one needed to shame another. Not in here. Not while we were kept busy with Sisyphean tasks. Some weeks it was cutting wood. Or digging peat. The worst was moving rocks across the field and then back again. Days might be spent peeling piles of mealy vegetables for our gruel. And blessed be she who found a stump of carrot amidst the turnips.

Every new girl was told about her. A legend when they came in terrified, more and more naive these days, because they’d never imagined it could happen to them. Newcomers learned quickly or vanished in a selection. The pretty ones had been carted off long before. And the twins. And any who’d let defiance poke through, even for a moment. Gone. To fates best left unimagined.

Every new girl was told, Save a little for her. She is saving our souls.

There was a special feeling to being close. Like you’d had a brush with royalty. Or a holy person. Long ago when people acknowledged other faiths I’d been taught about lamed vavniks, the thirty-six pure souls in every generation who wander amongst us doing good and channeling the divine. Was this the least likely place to find one? The most? Certainly the most necessary,

So the days passed. With toil, but also with laughter. And with laughter came hope, the most precious of gifts. Hope more precious than bread. Hope for After.

Girl with a Gun

When the papers said she’d killed three, I knew it branded her a terrorist. But the news had been so unreliable for so long that any such nuggets were precious. Any that showed a resistance not fully cowed, that is.

All I truly believed was that she was gone to us. Dead or disappeared meant the same. We would not see her again.

I honor her now by lighting three candles. Sometimes the lamp blinks in rueful acknowledgement and I see a glimmer of her smile. I knew she’d wanted more. Recalled how often she’d talked about her “baker’s dozen.” How often she’d said, As many as I can and the last one’s for me. I’ll go out smiling.

I’m sorry she’s gone, but glad she found her path, though it is not mine.

She was always happiest outdoors. Kayaking or hiking. Each day she trekked through local hills, avoiding people whenever possible. She loved road trips too. She was happiest packing her faithful hound, setting off for adventures; destination unknown, but unconfined. Open space all around. To see who was coming, and if they be friend or foe.

She told me once of a trip to Florida, and the woman who ran a charter boat. The day was warm and sunny. They saw many fish, though neither reached for a rod. They sipped cold coffee at dawn, wave watching as the dolphins guided them gleefully further and further from land. Finally, quietly, she’d asked about the woman’s scars: fifty ancient knife marks laddering any exposed flesh. Disturbing proof of life interrupted. Of a hard-earned after. And the brutality of her before.

Her own life had a similar dimension. Since bedtime on her tenth birthday, when her father, latching the bedroom door, delivered his “special gift for daddy’s girl.”

It took six years to create her own after. Six years dreading that damning clunk and all that followed. Six years closing her inner veil. Helpless as she lay shivering and alone. Six years hiding her rage, a constant burning that failed to warm her.

Her lanky frame held a coiled fierceness. A readiness. A ward-off cautioning any approaching hand. She left home at sixteen, with a duffel and no goodbye. Moved to a new city, where she changed her name and cut her hair to a nubbin. At first, she took only took physical jobs—landscaping or construction—imagining his head with each hard blow. But her anger grew.

There was often a lover. Even some deep and durational relationships, though most ended bitterly. Her heart remained guarded and taut. Frozen. Hungry for a retribution she could not name but which pulsed silently under every breath.

There were flashes of kindness, flashes of friendship, flashes of the woman she might’ve become. It was hard to say if she was ever really happy. But the anger reached stages of containment. She became a partner, parent, and friend. She allowed herself to care for others, and cautiously allowed people into her sphere. But as the world grew more and more unbalanced, her repressed rage found new voice.

She was unsurprised by The Upheaval. Had seen the signs, and, with her instinctive compass of survival, organized her life to live safely on the fringes, below the radar of social media, avoiding groups. Despite her prescience, she drew no pleasure from being right.

The anger was an eternal flame, but represented the opposite of peace. It was a constant, internal goad to translate her silent screams into action. To revenge her innocence, to accomplish something, anything, akin to retribution.

So when she told me she was buying a gun, I was not surprised. I asked, Have you ever shot one? She replied, Only in the arcades when she I was a child. Then added how she recalled wishing she could pop that toy gun right between her father’s eyes, a vision that felt important but thoroughly unattainable.

So she put herself into training.

In the beginning, she wasn’t very good. It was somewhat comic to watch video of her scrambling between bushes and shattered buildings, trying to evade and attack at the same time. But the more she practiced the more confident and proficient she became. Instead of futility, a plan became more plausible. A deadly plan that would end in her own demise, an outcome for which she had a little regard. I’m done, she said. My only goal is to take as many of them with me as I can.

She swallowed her anger in the places her enemies gathered. She was busy scouting, observing, preparing, She was monosyllabic in their company, but loquacious when describing them, dehumanizing them as they dehumanized her, without shame or guilt. It was simply how things were now.

When we talked about life before The Upheaval, all she could say was, I wasn’t happy then but at least I felt a shred of hope. Now I have none. It takes all I’ve got to keep me from shooting.

The last one is for me, she said. And said it often. She yearned for a showdown the way many of us search for love. The gun was her final answer to her father. It was the only reply she could imagine to the horrors witnessed during The Upheaval, a time when a generation’s work was undone by hatred and greed.

Almost anything could send her into an angry spiral: the news, seeming weakness in a friend, any new injustice enacted or uncovered. Once triggered, the rage was difficult to contain. Sadly, there was no shortage of bad news or fresh rage.

Slowly but inevitably her fragile social network began to dissolve from the strain.

Our conversations grew shorter, more stilted. She became less interested in anything except exhortation, urging everyone she knew to focus on exactly what made us feel so helpless and so ashamed of our fear. Slowly, but inevitably, our friendship began to shift. She scorned my cautions. I feared her growing militancy, as she decried both active collaborators and the silent.

When she felt ready, she made herself visible. Stepping from the shadows of her life she became a sentinel at the rallies and marches. Always in her worn fatigues, her hair newly dyed like flame: crimson at the roots and yellow at the peak. A lit match, daring to be struck.

Years later, when protests were but a sad memory and we were teaching brave young women in the clandestine schools, I heard stories. They called her The Guardian. Said how much safer they felt when she joined them. How she’d inspired them. How they missed her bright presence. I understood, because I did too.

After they killed her they tracked us all down. Anyone who’d known her, who might have been infected with her vigilance. It was three days of questions and denials, one bad beating, and a stern warning to “be a good girl now.” I was chastened but unharmed, though others were less fortunate.

A few months later she came in a dream. She was in her camo duds, smiling. I smiled back. I felt her breath on my cheek as she whispered, Eleven. I got eleven. And the last one was for me.

The Jacket

The neighborhood children called her The Crazy Lady. They alternated between avoiding her and slinking along behind as she crisscrossed residential streets, market areas, and even (defying every fervent parental instruction) into the industrial zones. There was never a discernible rhythm to her movements. No seeming logic about whom she approached, or to whom she offered her mysterious and occasionally terrifying rhymes.

The adults called her The Poet, because they heard in her blunt utterances and scribbled notes both truth and actual quotes from poetry. Language remembered from the forced memorization of youth, before The Upheaval, when English classes were cancelled, flushed with History as sources of troublesome ideas.

Those who knew called her The Messenger.

Usually she wrote. It was rare to have an actual conversation, although everyone acknowledged she was a useful observer to question if you’d lost your dog, wallet, or keys. The answer might not be obvious, but it likely would have the right clues.

Her messages weren’t poems in the meter, verse, or rhyming sense. They ranged from quote- of-the-day homilies to Shakespearean monologues, delivered with thunderous style and wild gesticulations. Often they were cryptic, delivered with a Mona Lisa smile and a cackle. Some locals dubbed her Our Delphic Oracle.

The ones who knew heard the encoded instructions. The others saw only the local loon.

She was visually iconic. Flaming red hair, rough cut and wild. A loping gait. Faster than you’d expect, given her short stature and rounded frame. Always wearing a bombardier jacket of worn and beaten leather, gray and shiny in some places, white almost to bone in others.

The poet had been gifted her jacket years before by an old activist, whom she’d met often at rallies. The kind we used to go to, when folks weren’t too afraid to gather or be seen. When she’d admired it, the old woman had said, It can be yours. But you’ll have to earn it.

The young poet shivered at the thought. She said Yes. Please.

For two days she moved rocks, washed windows, and did chores at the older woman’s home. Occasionally the old activist would say, Here, put this on, and give her garden gloves or a work shirt. Always something more fragile than the rich beckoning leather. They spoke of the beauty of language. Of words’ power to inspire or suppress. Of their sensual lure. Of the legacy they’d inherited, and how it was being strangled into extinction by those who feared ambiguity and dissent.

The activist cooked them a rich stew as a ceremonial goodbye. Prominently on the table sat a box so sturdy that she still uses it as a bookcase, in part to honor her mentor. She eyes the gift but wisely knows it is dessert. They eat slowly, savoring the stew’s rich complexity, talking about the past, the struggles they face now, and more so, of what the future will require of each. She was excited more than hungry, but the talk of social justice was sobering and inspiring.

After tea and almond cookies, the older woman moved the box her direction. Open it, she said softly, a quizzical smile brushing her normally flat lips.

So she did. And to her surprise, the activist’s old jacket was not inside. Rather, there lay a new jacket, redolent with tannins, stitched with style. Sturdy pockets on each upper sleeve, their flaps concealing squares of paper and two sharp stubby pencils.

The old activist smiled. Touch it. And as the poet touched the sleek black skin that met her hand, she finally understood what earning her jacket would mean. That with its strength and secure enfoldment would come responsibilities far beyond her experience.

The older woman smiled sadly. It is the best and worst of gifts. There are many choices ahead. If you accept, you will become a Messenger, a courier in this good and necessary fight. Her eyes brightened as she regarded the poet softly. If you say Yes, you will always be at risk. I was lucky, but that was Before. And After is not yet in sight.

Her voice lowered. You will probably die young. But, she added, her face breaking open into an impudent grin, You will be free. And that is the biggest gift I can offer. She laughed loudly. In a world that runs on fear, that freedom will be your salvation. In your jacket you can be anyone. It can be skin or costume. You choose the face you show the world, and it will protect you. Until it cannot. So choose the life you wish, for nothing is certain but its end.

She stopped. Looking across the table, she asked the poet, Does this sound like what you were seeking?

The poet grinned cheerfully. If I’m joining the circus, I’m going to be a clown. The crazy fool. A holy warrior in the battle for truth. I’ll make myself impossible to miss. Hide in plain sight. And tell anyone who will listen what has to be done to make After become Now.

They grinned at one another.

You will earn it well, said the old activist. Make them pay attention. Her eyes crinkled at the corners. And make it fun. Our laughter is what they fear the most. It is our most enduring weapon. And it will eventually wear down their evil, though we may not live to see After.

The Lodger

He didn’t tell me his nephew worked for the resistance. Just said he was a kid from farm country, who’d gotten into the U on a sports scholarship. But he was quiet and didn’t want to live in the dorms. Needed a safe place to chill between workouts and classes. In addition, he said with a twinkle, the young man was a martial arts champion, with experience as a bodyguard to a minor rock musician. He’d be perfect in the cottage, once my ex’s detritus was cleared out. Even offered to help, and did. It easily solved some problems, so I didn’t ask the questions I should have. Ok, I didn’t ask anything, other than, Does he like to weed? Yes, I was too painfully naïve.

It seemed like a great idea. For a while. Having a strong young man in my sphere offered a heightened sense of safety. An illusion perhaps. But comfort for the heart is harder to come by these days. It’s overfilled with internalized dread. Horror about all that’s happened and fear about whatever’s coming next. Not me yet, but nothing in life felt assured. It had been so very, very, long since I’d felt safe.

After the world collapsed into hatred and guns, I’d retreated. Home and garden, books, teaching, streaming and mindless scrolling. All designed to ward off the persistent encroachment of darkness into my already over-agitated neuroses. Some days it worked. Others, my efforts felt laughably futile. Many nights I did not sleep. So his presence became a more solid anchor, a presence to ward off the monsters lurking in the dark.

I didn’t learn until later what they really did. My friend, a conductor in a new kind of Railroad, and my Lodger, who majored in things I wish I’d never known.

He moved in with a bulging duffel and some battered boxes. The first week I barely saw him. I think he was unsure what was allowed, and had been cautioned not to disrupt my equilibrium. I got used to his quiet comings and goings, often at strange hours. He was young, and it had been years since I’d been around those rhythms. I just assumed he was working out or studying.

After a few weeks, life normalized. We settled in, circling with increasing ease like dancers in a well-choreographed piece: sharing space, but giving one another the room required to live as though no one was watching.

It was a little strange and also fun. It was extraordinarily useful to have a human jar opener on tap, or someone to reach the tall places. He was soft-spoken and deferential, with too many Ma’am’s and Please’s and Thanks you’s. He gave me no reason to doubt neither his sincerity nor likeability. But though he seemed open, there was a watchfulness about him, an undercurrent of vigilance I felt cautious to question. I wrote it off to shyness, and to a life lived very differently than in our busy college town.

So I decided to mother him. Invited him on Sundays. We called it Laundry Dinner, because the dryer I’d put in the cottage could rock all night and eject towels still damp at sunrise, while mine actually worked. After a few polite refusals, he accepted warm laundry and roast chicken dinner, surprising me at the door with a basket of rolls so light and tasty I was shocked.

My MeeMaw’s recipe, he demurred. I can make that, veggie soup, and mac and cheese. Patting his flat belly, he added, Good for what ails me.

It became a ritual. At four on Sundays, he brought his clothes and part of a fabulous meal. We sat on the back deck in summer watching the sky, and by the woodstove in winter, talking about the ways of the world as his linens rolled softly dry.

We traded fabulous book recommendations. He quizzed me about Ta-Nehisi Coates and Colson Whitehead, and we wept softly together about the history of slavery. He knew more than I ever would about discrimination, access earned at birth. I shared Richard Powers’ The Time of Our Singing, which I’d listened to incredibly slowly, to savor its beautifully elegant language, and the education it offered about both music and the oppression of both our peoples. Of the dead and disappeared in our own times we commiserated carefully, with grim frustration and awkward painful silences.

He’d grown up knowing only tropes about Jews. He’d never known our struggles or heroes. I told him my family history and why I keep a photo of Anne Frank by the door. Then I remembered Nathan Englander’s story What Do We Mean When We Talk About Anne Frank? It’s an American/Israeli version of Whatever Happened to Virginia Woolf until it cracks open. When they get to the punchline, Who is the righteous person who would hide you?, I lost it and started to cry. Johanna was always that person for me. And now she’s dead. Eff you ALS! He watched as I crumbled, and put out a tentative hand to steady me until the tears subsided.

I saw him come home one night in the wee hours. I’d woken to pee and something moving in the yard startled me. I saw him crossing by moonlight, a long thin case slung along his back. I watched as he moved the garden carts aside and slid it under the decking, into a hidden cavity I’d never seen. There was no mistaking what it was.

I was suddenly very afraid. Should I say something? Say nothing? Ask him to leave? Ask how I could help?

It seems I’ve become a Johanna, albeit a scared and reluctant one. In a different struggle. In a different time. But the same enemy. The same evil. The same grim necessity to do things we never thought we could. Who will I be now?

I’d grown up on the stories of targeting and escape. Of my grandmother’s cleverness when they came to arrest Opa Oscar, telling them he was sick from his WWI wound, received fighting for the Kaiser. The transfer of property and valuables to a trusted employee while they organized their exit papers, leaving behind all but their lives. Two hours into Brazilian waters, I learned at my father’s funeral, when the war began. Only two hours slower and their boat would have been returned to the charnel house of Europe. And on my mother’s side, how the house in which they were celebrating Passover had been set ablaze with them inside. So I knew what was at stake for us all.

But this was my quiet settled life. Was I ready to put it at risk? Had I already crossed a line? What direction would I go next? And how far was I willing to travel?

I worried the questions for weeks, afraid to discuss them with anyone, so painfully aware was I that these days the most critical commodity in our lives was not money but trust. Despite a tightly winnowed circle of friends, an instinctive caution kept whispering. What if? What if? What if they tell anyone?

This is how societies crumble. This is how good people go mad.

Then it was settled, though I felt like a coward when I read his good-bye note: Thanks for the hospitality and for sharing your good heart. I’ve moved on to keep you safe, because I know you know. I hope evil stays far from your door. But I’m glad to know you, and to know the way back. I hope never to need your sanctuary again. No matter what, hold this truth: Despite your fears you will rise up strong. You are braver than you know.

I cried with relief and with shame, because I believed in myself so much less than he did. I was afraid to be tested. A sobering future loomed, enhancing all my doubts. Would I turn him away if he knocked, or would I surprise myself? What am I really made of? And how will life force me to learn?

I was filled with questions. Only time held the answers.

I prayed my Lodger was right.

Mythologies

It began as it ended, with whispers and rumors. The ephemera of truth that framed their arrival and departure. A cloud of mystery that magnified their impact on the jeune filles of the city. And also on their mothers, hungry for the adventure and magic that the shop and its mysterious new owners proffered. It was a refuge for some and the promise of a new life for others.

A short, smoke-darkened alley paved in cobblestones, born in earlier, simpler, times. Apothecary, bookstore, and dressmaker neighbors who lived above their shops. Tall gabled homes, shutters always closed, occupants seemingly evaporated. And the corner café that opened to the city, acutely brighter and busier than their small world. It was like a thousand others: small streets, rebirthing in this decade of large possibilities and larger omens, both promising and dark.

First came the sign. Silver lettering painted in a stylized font on a swinging ebony board: Mythologies. A winking bronzed owl peered from above the doorway, silently asking visitors what dreams they hoped to encounter. Windows and door were shrouded in drapes of an exotic weave, intricate arabesques in blues and burgundies shot through with golden threads, promising something special, exotic, and rare, yet to be revealed, but for which passersby began to hunger.

In later years everyone knew what was to come. Four times a year the mysterious sisters whose shop had sparked so many stories had their openings. The reveals began at sundown on the equinoxes and solstices, after they returned from their travels. Their travels from…from….From where this time? Always the question.

In the days before, those who knew were awash with rumors. I saw Hilda at the market. She was wearing harem trousers! Or, Carola was wearing a kimono at the café. She was sipping saki! It became a guessing game. A battle of wits and honor to discern what culture and stories would be at the center of the next collection.

They’d arrived in ’34. Compact, dark-haired, clearly sisters, speaking in Teutonic accents. The dusty leasing sign was replaced with a small notice: Nous sommes arrivez. Attendez…. (We have arrived. Wait….). The shop freshly painted. Then Mythologies’ sign. Then nothing for several months. The unveiling was a slow dance. Many vans packed with boxes speedily dispatched inside. Large crates with mysterious labels. Matilde the dressmaker heard the postman comment how much his son enjoyed the wildly colorful stamps that accompanied their correspondence.

The advertisement for their shows would appear on solstice and equinox mornings. Just a simple, black-bordered advertisement, with the winking owl smiling at the reader, and the words Ce soir (tonight). Opening mornings saw a mix of curious passersby, though the curtains remained resolutely closed. The cafe at the corner did brisk trade, while dozens of eyes watched the windows. They never parted before dusk.

Their first event was glorious, after a carefully placed notice in the daily paper: Mythologies. The first. Tonight. After moonlight. In your finery please.

The shop was lit with the gleam of a thousand crystals reflected in chandeliers, mirrors, and candelabras. In the center was a sort of altar: an oversized, round pedestal table, surrounded by stacks of cracked leatherbound books, mysterious figurines, and bright flowing fabrics. It was topped with a marvelous antique globe, countries named in an unreadable script, and oceans decorated with fabulous monsters and balloon-cheeked zephyrs promising swift passage.

By the door, a tree of scarves in colors from fuchsia to peacock, lemon to aubergine. A sister greeted each guest entering for the first time, held her hand and gazed for a moment into her eyes. She adorned her guest’s neck with a light brush of silk or the warm safety of fine wool. None could imagine receiving a gift different than what had been chosen for her. They preened with delight.

Entree, they were invited. Listen for what calls to you. And then, four times a year, they were thrust into a world of exotic curiosities and treasures, each a surprising counterpoint to the last.

The very first focused on The Holy Land, defined loosely from Constantinople to Jerusalem. There were prayer books in myriad languages, texts and reliquaries from the major religions and many minor ones, and a wall of finery from flimsy harem silks to full-length chadors, inviting dress-up, adoration, and dreams of travel. Small journals, random photos, and bundles of old letters pressed against beautifully embroidered linens. Open steamer trunks and suitcases were strewn about, filled with a cornucopia of jewelry, trinkets, and curios. Tempting valuables were intermixed with baubles and intricate little puzzle boxes. Touch us, they called silently. We are here for You!

There were many discreet nooks for a guest to disappear into. A cozy chair by a bookcase filled with well-worn gems. A vanity with perfumes, lipsticks, and mysterious small vials. A mirror surrounded by masks. And a large buffet along one wall, piled with a tempting array of foods, many new and curious flavors, with a tall central pyramid of baklava glistening in the candlelight.

Though the timing and rituals of notice did not vary, each opening was unique. The gifts at the door changed but being gifted did not. Sometimes guests would be given a tiny teacup with an exquisite new blend, or a tiny folk-art doll, or a special small crystal. Always at the holidays, they were gifted superb chocolate, for which the sisters had an inordinate fondness. They delighted in surprising their clientele and that delight was reciprocated with patronage and friendship.

The Japanese opening had walls lined in kimonos of the brightest silk, and paper umbrellas suspended to form the shop into an eastern hideaway. The air was filled with elegant tinkling music; the sideboard offered exotic rice dishes and rough clay cups of warm sake. The first Christmas was all reindeer bells, mulled wine, and runes. There were openings for the mysteries of a Moroccan bazaar, the delicacy of Vietnam, and the vivid brilliance of the Hispanic world. The globe began to collect tiny flags with dates to commemorate each opening.

No one dared leave town until after, lest they miss the best parties of the year. Becoming a regular at Mythologies meant one had arrived.

In the beginning they were more insular, but slowly began to invite their neighbors up for tea. Their apartments were accessed by a narrow hall and steep stairs, beveled from centuries of feet brisk at the bottom and weary by the top. Slowly, between travels, they forged the rituals of friendship: Sunday meals, farewell and welcome home gatherings, marathon card games, good wine, and late nights talking and laughing. And so they created family.

Carola, the elder sister, was more reserved and cautious. She handled décor and food for the festivities. There was a permanent air of sadness about her. Invisible nets of mourning seemed to envelop her. Her voice was soft, and she carried an air of fragility that those who learned her later came to realize was an effective ward against anyone she wished to avoid. Inside she was steel. She was a caring loyal friend and an amazing baker. She grew close with Mathilde, because they shared a dark reserve about both past and future. Their silences spoke as much as their words.

Hilda, the younger, was their ambassador to the neighbors. Also the fixer when they encountered any problems in their new country. Her best friend became Gabby, the bookseller next door. They took delight in sharing their favorites in every language, and became extra playful after a few sips of Gabby’s special fruit wine, the fermented family secret of centuries. When Gabby needed time with her lover, Hilda ran the bookshop, surprising them both with her literary knowledge and success.

Mythologies’ most cherished rituals were for the young women in their chosen circle. After a girl turned thirteen, she was honored at the next celebration. Crowned with a garland and feted, she was invited into the alcove with a beaded gypsy curtain. She was allowed to choose a bracelet from a special collection and her first charm to affix to it. She was told the secrets of womanhood. When she turned seventeen, she was told what every woman most needs to remember: that she was worthy of happiness, and that she must walk away from anything that did not augment that knowing, no matter how scary that leaving might feel. Then she was given her last charm, a small winking owl, that would forever gain her passage and support among their coterie.

As Mythologies became an established ritual, they developed more than a clientele. They developed community. The young women started a betting ring about which culture would be at the center of the next event. They went to bed dreaming of the treasure they would find, and the beguiling objects that had traveled across seas and sands to find them. Their mothers brought them for the breath of culture it offered, and because the sisters treated them with a respect they did not always receive elsewhere. The shop offered refuge and safe harbor, and dreams of escape.

The exhibits lasted a month or less, until the sisters departed for their next destination. The store was kept safe by the local urchins, who had a special knock when they needed help. We’ve been hungry too, said Hilda. Carola always had a roll or a cookie for those who asked. They kept a small room in the cellar with clothes and bedding for those who needed it, and had helped several of the young women off the streets and into school. The sisters were loved.

When they returned from abroad, friends would be invited for supper. Each was given a special gift, usually a good luck charm from wherever they’d just been. Gabby joked, With all my hamsas I will be safe forever, so let’s have an adventure! The foursome became an unusual but supportive family.

There were, inevitably, the questions. And the sad answers. No, no family. No children. No spouse. No parents. More shakes of the head. No longer, was all they would say. That was before. The moment of stillness. The knowing. A subject not raised again.

Everything changed when the city fell. The curtains were blackened, permanently drawn. Our travels are over, said Hilda sadly. But our work continues, added Carola, as Gabby and Mathilde nodded. Standing on the rooftop with the darkening city splayed before them, they heard the sound of the advancing army and made their pledge. The conversation was short and mutual.

We will fight them. Quietly. Daily. In our fashion. With our people. Until evil is gone and goodness returns, we will fight.

And so they did. For four years they ran a network that sent vital information and endangered resistors out to safety. They shared news from their wireless, both the tragic and the hopeful. They reassured everyone who turned to them: Yes, horrid. But the demise of evil is assured, if we persist. That knowing is our best source of strength.

They were vital and effective until ’43, when they were betrayed. But for any who’d known them, simply saying “the sisters” offered hope in the times that followed. And for some, that hope was enough.

Night, Night

She would never have said, Yes, I’m afraid of the dark. In fact, she was not afraid. She simply ignored it. Behind closed lids and with the clutch of her familiar stuffed bear, she was somewhere else. Somewhere safe.

If you’d asked why she read herself to sleep or awoke often past midnight to the blur of an old movie, she’d probably answer with some story about what an improvement it was over her sophomore year in college, when an indulgent roommate regularly pried a Russian-language dictionary from her leaden hands. The conversation would likely wander to tales of her intensive-language course a long and humid Indiana summer ago, or the time when she and a grad-school friend had taken off for Grand Canyon in search of escape and enlightenment. A conversation leading anywhere but her hidden truths.

A seemingly average life. Average, that is, if one ignored what made her family different: immigrants from a culture intent on killing them. A life of exile and murdered relatives. Futures sacrificed to survive, ensuring safety, she was taught, if one observed life’s careful rules. The rules for immigrant Jews: blend in; don’t make waves; avoid trouble in any form. The rules for a woman: don’t speak up or out.

From a duplex to the suburbs. First car an uncle’s cast-off Buick. First airflight at fourteen to visit her best friend, whose parents had moved to an hour outside Pittsburgh. To the day when the jet lifted from La Guardia, curling westwards towards L.A., to a future whose veil she could not pierce, despite her sense of large and imminent change.

She’d always been a reader. Book as toy. Book as window. Book as wall. From the silent pools of childhood, a visual memory: her father in his easy-chair, reading the Sunday Times; mother asleep on the sofa, one arm trailing, book rising and falling with each breath. She and each sibling in a different corner, reading themselves away. Her adult home is filled with books, savored like great food reviews. She touches their spines lightly, the way others tease a lover’s nape.

Her eyes droop earlier now. She knows that what can be learned from others is not easily written, and less easily understood. So she’s begun to write her story. To explore the curious line between memory and truth. If something really lurks in the dark, perhaps she will meet it. It’s as close to risk as she dares.

She chills at each blank page. Sometimes she walks away. Sometimes she surrenders to the slowing, to the pause before the words begin. Without form she’s free to wander. No illusions of a novel; she knows herself too well. Each finished story is a triumph. The beginnings of others a lure. Cards pulled from the deck of her life. See how the pieces touch, where their edges form and fit. What truths define her or set her free.

Writing lets her question. Her curiosity has roots. But her memories have fears that the writing unleashes.

They’d emerged last fall, after decades of denial. At first shadowy and nameless. A sense of discomfort reading stories in the paper, persistent insomnia, an aversion to people who talked about their childhood. Then she had the dream. At least that’s what she called it on waking. But it was different enough that she was troubled for days.

Only once before had she felt something similar. It was, as she said in those moments of shared confidences that came too rarely, as close to a UFO encounter as I ever expect to have. It happened one night ten years before, in the bed she shared with her snoring partner. They’d not been intimate for years, and she shared more affections with the large dog who nested between them.

It was a sultry summer. The curtains blew an occasional breeze towards her restless form. Her body arched towards the air, though it neither cooled nor refreshed her. She remembered awakening quickly, startled, a cold sensation on her spine, like it had just been unzipped. She clung to that idea for years. Unzipped, she would say. Un. Not zipped back up. Not closed. Not after. Not helpless. Only just unzipped, as though she had foiled the intruder before anything malignant had occurred. As though her psychic sensitivity had protected her from invasion, from an unsought encounter.

She tried to put the dream away. But the feeling did not leave her. She felt opened, exposed, vulnerable.

So she recognized the sensation when it came again. This time there were no mysteries. Not even the illusion of a foreign entity. She awoke in an instant, the image tattooed on her soul like the brutal blue number on her grandmother’s arm.

She saw a man. Worse, a man she knew. She kept telling herself it could be any man. Might be someone who looked like him, might not really be him. But in the voice she could not silence, she saw his face and knew him. Saw his face and named him. They stood in a frozen tango. Like characters in volcanic ash: his hand outstretched; she petrified in fright, at once her adult self and the terrified child she felt inside.

He didn’t really touch me, she told herself, for this she could never share with another. I mean we were just standing there. He might have been showing me something, might have been explaining something, or answering a question.

But nothing explained the icy chill she felt when she saw his outstretched hand, saw the long tapering finger reaching relentlessly towards her. Nothing could make her forget the feeling of her spine being slowly unzipped while he spoke to her, murmuring in a soft and hypnotic cadence. Nothing could erase that sense of her spine sliding back into place, deliberately, one vertebra at a time, until there was no outward sign of change.

Afterwards nothing could warm her. And no one could rock her to sleep.

Old Family Recipe

Take a daughter and her mother. Put them in the kitchen. Allow to thaw to room temperature. (Note: They were frozen long ago, so there are white and crusty places. A few knocks and rinses; who will know? All family recipes have evolved in the diaspora, so please expect flavor changes from your memories of childhood.)

Assemble all dry goods: Many unasked questions. Decades of silence. Knowings they cannot forget, no matter how they might try. Words said harshly or in anger. Crumpled notes, unfinished, mixed in with those received and read. A mutual epigenesis of fear. (Note: Generations of brittle emotions, left too long in the back of the cupboard, may require extra leavening.)

Assemble liquid ingredients: Blood. Shared YY chromosomes. A long skein of intuition. The tears they shed alone. The few shared and witnessed. Questions too long unasked. Secrets so long unspoken. Too many missed moments. (Note: No eggs, a dying ancestral line.)

Hold the following in reserve, adding as needed: shame; guilt; yes, yet even more sadness; and all the unspoken truths whose acknowledgment might shatter them. Look at their hands, resting on the counter. One more gnarled, but the same long fingers, blue veins coursing beneath their careful silence. Hands that in another world might have made music or art. Look how surely each grasps the knife. How deftly they can knock a carrot into shape, whittle a cucumber into tempting bites.

Do you remember, the mother asks, when Uncle Paul helped with dinner? And they laugh together, shoulders almost touching, a brief ribbon of connection. A man of 65, clueless how to use a potato peeler!

The story settles them. The urge to flee retreats, sits watching from a corner. Waiting.

They work together wordlessly, assembling and gathering. Doing has always been a ward. An organizing metaphor to hold the darkness at bay.

Among the daughter’s first memories: age three, firmly grasping the stirring spoon for marble cake, the family’s go-to dessert. Her face smeared gleefully with chocolate, eying the dripping beaters with early lust. Before she learned that sugar is not love, though she searched well and long for happiness in that elixir.

Had she one day with her mother now, the daughter tells her friends, she would spend it in the kitchen, asking all the questions that layer their history. Culinary first, but then perhaps the deeper truths, the ones not surrendered into pan scrapings or denial. The lost secrets of a fluffy omelet laced with grape jelly, a weekday surprise when her father worked late. Or of the mysterious Cold Lemon Soup.

She’d asked the mother once how it was done, this cooling summer meal that freshened so many hot, firefly-lit evenings. Oh you just take some lemons and some water, the mother had replied, her voice trailing. That’s all? the question came. Silence. Then… Well, yes, you need some sugar too. More silence. And you can use some wine for the water. Just taste it. You’ll remember. But it wasn’t enough; the daughter never did.

Such vagueness evaporated when the mother was in her kitchen, yellow and sunlit, generous in space and tools. African violets and bright watercolors. Gingham curtains. Deft displays of multitasking long before the word was coined. Veal stew simmering; beans kept green; iceberg wedges chilled (Note: Decades would pass before artisanal greens graced our microbiomes.)

The mother’s mother’s cooking was a dreaded Sunday obligation. Mandatory, but hard to swallow. Canned beans boiled to a gray sludge; chicken tough and stringy, long bereft of nutrition. All dry and tasteless, but eaten in gratitude that the chef de cuisine had not perished in the ovens like her six missing sisters. Eaten under the footsteps of her upstairs boarders, refugees from the same history, whose very presence had kept them housed after the grandfather’s death, just two days before Pearl Harbor. (Note: The daughter’s mother had thought the boisterous parade was for her father, a laughable value for just one more dead Jew. Despite all, there was yet some innocence in her.)

Cooking was the mother’s defense: her pride, her offering. She gave what she could, with food as her alphabet. She had mastered baking first, to add some sweetness to their immigrant lives. She’d saved her meager pennies for the trolley, walking instead to her second and third jobs, taken to keep her young brother, the genius, from being wrenched from school and apprenticed to the tailor. Then she’d bake sweets for the family. And the boarders. A drop of sugar in a sea of grief.

She started her first menu binder in a notebook from her abandoned high school studies. In the margins were sketches of the buildings she’d wished to build, in her fantasy career as an architect, dreams dissolved as she took up the burden of supporting her family. (Note: By her death sixty years later there would be dozens of binders, reams of paper exploding from them, without any organizing logic. The mouthwatering detritus of a thousand food reviews, from the local paper to gourmet magazines. Too many for any lifetime, including the daughter’s.)

Slowly she turned to the daughter, now a grown, accomplished woman, with a career and life partner. Albeit no happier than her matriarchal lineage. But with the middle-class trappings of a life lived far from the brownshirts who’d terrorized the mother’s childhood.

As they unwrap the pounds of sweet cheese that would become a pillowy rich dessert, the daughter recalls the worst of these: her mother pulled from the back of a public bus, her braids forcibly cut, school notebooks dumped in the gutter, and pages of her beloved Rilke anthology, torn one by one from their binding by laughing goons, sent aloft into the winds of history.

The daughter lives far from the pain of the old world. Even her early memories are sparse, but many punctuated by scenes of her crying mother. Walking out of a room mid-sentence as her voice broke. Quiet among her circle of friends, all alumni from the same brutal adolescence, some tattooed with the blue ink of nightmares. In a crowded family gathering, always safe only in the kitchen. Her mother always on the edge, an unknown instant from cracking open.

Her mother always in service. Always seeking absolution for unknown fears. Gifting baked treasures like bribes to a border guard, a means of finding safe passage when none seemed possible. The mother close to breaking, held together by brisk routines of doing and more doing. (Note: She did break, and sometimes with great drama. Those stories are more complicated.)

The family mantra: Don’t do anything to upset your mother.

The daughter recalls her first time in the kitchen. It’s an early memory, almost as old as sitting on the slanty cracked concrete of the front stoop, watching their neighbors walk by. Neighbors who looked at them coolly, with bitter, only marginally subdued anger, recalling husbands and sons never to be seen again, sacrificed to save these newcomers, these strangers, these outsiders, these immigrants.

The cooking memory is visual, kinesthetic, and olfactory. Cream puffs. That oddly thick yellow batter. Stir more, her mother had said. Stir until you see the holes start to appear. Then keep stirring. She remembers the wonder. That something so sticky and heavy could transmute into such open airy places. Crust for crunch, crevices for a tongue to explore, and the sweet satisfaction of richly whipped cream.

In such a lineage, each had chosen silence. Silence to hold the sadness. Tears held back like rivers damned. Emotions taut but private. No succor asked for, given, or even offered. But here in the kitchen their rhythms find each other. Like dancers who know when the beats will come as they reach for the needed tool or ingredient.

Wordlessly but with practiced grace, giving each other the space to lean in. Or away.

In a burst of efficiency, they work. Creaming the sweetness until the batter is silky, pouring it into the waiting crust, and retiring to the garden, each with a book, the family’s traditional escape, while the cheesecake reinvents itself.

Later they will sit and sip their tea, their bodies an unconscious mirror, each melting into a chaise, but one foot resting on the ground, poised to flee if needed. A slice of cake beside, still moist and warm. The hidden splash of Cointreau their secret recipe.

Each wears a small smile. Not quite triumph but more than survival. However slightly, they had narrowed the gap. Not with soul talk. But with food, the family’s acknowledged currency. To be enjoyed among the marigolds and nasturtiums. To stare in wonder together as cardinals embrace the feeder, and a lone fox skitters among the hedges. To let its creamy richness mend them from the inside, however briefly the respite.

And as those afternoons together knit their stories closer, each acknowledges the primary truth of their connection: that they are necessary but important mirrors, and that the angle of reflection will always be blurry. That they are bound by their history, and that knowing will always hold them, however uneasily, in this awkward dance of life.

Schrödinger’s Jews

They arrived later than they’d planned and saw a large noisy crowd, all aimed for the narrow doorway. Everyone was pushing and shoving, so they jostled their way in and held a tight trio in the throbbing space.

I’d wanted a drink, said Einstein with bemused patience. But I can’t even see the bar.

Ever hopeful, replied Heisenberg. Close your eyes and imagine beer. Are you less thirsty now? Schrödinger laughed. And who would know?

As more enter behind, they’re pushed deeper into the long narrow room, already crowded and quickly filling far past capacity. They hear cries of Please! and Water! but see no serving staff. The murmuring flows around them as they hold their small piece of real estate.

When it’s clear there’s not one empty molecule, a harsh screech punctures the air: large metal hinges snapping firmly into place. A giant unseen hand upends the room. The floor rumbles beneath them as they lurch forward, defying any known gravity.

Einstein mimes playing the violin. If only we’d brought our instruments.

Schrödinger barks harshly, So we’d be three cool cats in an overcrowded box? Says Heisenberg, A box, but not a true solid. See the slats up the sides? And feel the faint breath of wind as we gather speed? This, gentlemen, is a conveyance. An express ride to our future.

Our future where? asks Schrödinger.

It’s all relative, smirks Einstein.

The boxcar gains momentum as the physicists take stock of their small new cosmos. The track rolls under them with relentless focus as murmurings become aggravations. Cries of increasing distress assail them from all directions: Water! Air! Help! Now! My mother! My father! My child! My child! Oh God in Heaven! Why? Why? Why?

Let me tell you a story, says Heisenberg. There was a kind and pious couple. He was a doctor and she a teacher. They lived simply, helping friends and family make happy safe lives. As the world grew darker with anger and hate, they watched so many wrestle with leaving, with how to resist, and with the shame of keeping silent. They persisted with goodness, even knowing they would eventually become targets.

The three nodded in knowing recognition. Quipped Einstein, No special theory needed. In a world of evil, they always try to kill the good.

Heisenberg continued, As the world narrowed, they faced an inevitable choice: how to answer The Knock? He paused. The sounds of distress were more muted, as though many were listening. When they saw the signs to report to the train station, they hosted a special Shabbat dinner. Dressed in their finest, they roasted a plump chicken, drank the best wine, and shared tears and blessings with friends. The meal ended with brandy, chocolates, and embraces. After the guests departed, they lay down on their bed, held hands, and took the pills that would guide them to the world to come.

He paused, letting the crying and tears that surrounded them fill the void. Then he turned, eyeing Schrödinger with a collegial challenge. So, when the Nazis knocked, were they living or dead?

Schrödinger bowed. The right question. But here, perhaps, is a better one: When were they fully alive?

He took several deep breaths of the decaying air before continuing. Before the Nazis changed the world? Before they decided which world to choose? Aren’t we all on the track to death? Do the fearful die more cruelly than the brave? What defines courage?

And, added Heisenberg, turning to Einstein, perhaps the Eternal Now is most relevant. What about us? We here? In this box?

Einstein lets the question settle into the darkening gloom. The smell of death surrounds them, weighted with the tears and prayers of their cattle car companions.

Shaking his irreverent silvering crown, he declared, We are three particles caught in the indifferent wave of history, careening down these tracks in a miracle of Teutonic efficiency. He looked at his companions with gentle appreciation.

We transition from known to unknown. From matter to energy to light and back again to matter. We bridge creation and eternity. We are alive because we are the story. The whole story, in all her wisdom and banality, truth and frustration, and holy courage.

His soft eyes blessed the enveloping gloom. I cannot change history, or how she treats us. But this truth holds always: If we tell our stories, we are alive. While the stories live, there is hope. And that hope is life’s greatest legacy.

The Missing Letter

We’re all hoping for better. Preferably soon. And it would be lovely if it felt and tasted good,

was comfy and friendly, with room for our beloveds.

Many spiritual traditions have a concept of The World To Come. It ranges from a Christian

heaven to a Jewish post-Messiah utopia all the way to Hindu ideas about reincarnation. It’s

seemingly sequential, a “what comes next” after what we perceive as “now” or “real.” Often

with a healthy dose of “if I was good” or “if I obeyed the rules,” some consequential reality will

follow. Perhaps because most of us fear complete randomness almost as much as we hate

losing control, whether that’s “Fate” or that we might be living in a simulation.

In the mystical Hebrew alphabet there’s a hidden 23rd letter. It’s supposed to represent that messianic age, the

hope that there is a better world, that we might indeed ourselves be worthy, if we survive this

latest tragedy of heart or body, that our spirit will once again remember to soar.

As I began these stories, the first when the world turned darker, I thought about how Hebrew

prayers often have a hidden code, where the first letter of each line forms the alphabet, with

the implication that at the end of each prayer somehow we’ve invoked freedom from war and

want. If only true prayer made it so, and if humans weren’t greedy, jealous, angry, and fallible,

to name but a few.

So I decided to see what my native tongue, English, could offer in that structure. And here we

are, at the end. In the hope that stretching our hearts and minds a little has edged opened the

crack of the new dawn. That the darkness will not swallow the light, and that we will wake

tomorrow determined to become what we and the planet most need: to care, and to help one

another.

My hope for After: That we can become our best selves, and together create our world to

come.